Case study from The Museum of Jewish Heritage, New York and Jewish Museum Berlin

Graduate school paper from Museum Studies program, Collections Management course, City University of New York, May 2022

Inter- or transgenerational trauma takes place when negative historical events such as genocide, war, colonization affect a population of the country resulting in traumatization of not just one, but of every succeeding generation. Because of the temporal aspect of this type of trauma museums represent most suitable social labs of addressing, documenting, analyzing and studying it. In this regard two museums could serve as a case study for two different aspects of this multifaceted topic: how a museum presentation can successfully address trauma while staying conscious of visitor’s needs and how permanent collections of a museum could contribute to our understanding of trauma. First question uses ongoing exhibition Boris Lurie: Nothing to Do but To Try at Museum of Jewish Heritage as an example. The second question looks at the collection of Jewish Museum Berlin.

The tragic aspect of the Jewish heritage pertaining to the Holocaust is used in this paper because in contrast to other sociopolitical traumas experienced by the mankind Jewish historical experience has been sufficiently researched, studied, and documented in an institutional context. More conclusive observations could be formulated when looking into the Jewish trauma in 20th century as represented in the various Jewish museums as compared to the institutional representation and analysis of the American slavery, Communist purges of Eastern Europe, the South African apartheid, the Armenian or Cambodian genocides that all still need firmer grounding in terms of curated exhibitions and audience responses.[1]

As a term trauma is used in medicine, psychology, history, and other social sciences so it is pertinent to start with a workable definition. Over time museums have become battlegrounds for representation of the past and a dominating narrative of collective identity. Hence traumatic events that could be defining for a nation or a community are highly charged topics and “traumatic memories in processes of representations of collective identities seem to be predominant today.”[2] As Marianne Hirsch discusses in her vast research on memory in the context of the Jewish studies and the Holocaust, memory transmission takes place in two distinct ways. Group memory uses family as its mechanism and is intergenerational by nature, national/political and cultural/archival memory is trans-generational as it communicates through symbolic representations.[3]Understandably institutions mediate this symbolic representation even further by providing their own socio-political and cultural contexts and focus.

It is then institutional responsibility to forge direct connections to the past, “to reactivate and reembody more distant social/national and archival/cultural memorial structures by reinvesting them with resonant individual and familial forms of mediation and aesthetic expression.”[4] Re-discovery of such links through aesthetic, but also well-researched presentation becomes paramount as Second World War recedes in our collective memory and younger generations start to forget it or being non-Jewish do not learn it in the first place. In her comprehensive overview of post-Holocaust Jewish museums in Europe historian Ruth Ellen Gruber discovered that these museums were mostly acting as symbolic representation of a lost civilization, “ritual objects, artwork, documents, books, and Judaica, but also everyday objects, which in the all but total absence of living Jews, were elevated to the status pf venerated artifacts.”[5] Over time this type of symbolic representation came to be dominant mode of representation in contemporary Jewish museums across the world, absence of generations are emphasized by the artifacts and archival materials they left behind. Yet, this symbolic engagement has shifted to include more contemporary contemplations on various artists or movements or themes, emphases on the aspect of absence is always present. Two examples discussed below support this view.

Boris Lurie’s (1924-2008) ongoing exhibition at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, New York reintroduces Lurie’s story not from a more familiar standpoint of the1960s non-conformism American artist, but his story as a victim and survivor of the Holocaust. Lurie grew up in Riga, Latvia. The Nazi invaded Latvia when he was 16 years. After a short imprisonment in a ghetto Lurie’s grandmother, mother, beloved sister and girlfriend were executed in the nearby Rumbula forest. In a matter of a few days 25,000 women, children, older and disabled people likewise perished in the forest executed by the Nazi Einstadzgruppen (Mobile Killing Units). Lurie and his father have survived imprisonment Buchenwald and several other concentration camps. In 1946 Lurie immigrated to New York where he became a tireless advocate, artist, researcher, writer, always fighting to draw attention to the Jewish tragedy.[6] The exhibition in New York focuses on Lurie’s series of drawings titled War Series and presents around hundred paintings and drawings as well as photographs and archival footage, all engaging with his tragic earlier years, an experience reverberating throughout the artist’s life. The selection of the objects was formulated by the exhibition curator Sarah Softness based on the museum’s interest in: attestation (bearing witness), ambivalence (doubt, contradiction, irresolution), and advocacy (writing, research, legacy).[7] All three-address intergenerational as well as transgenerational trauma that Lurie has experienced in direct, but also nuanced way.

On the one hand, the museum presents narrative known from many other sources, but by looking in depth at one particular story and helping visitors to have an empathic experience through the presented artworks and archival photographs this exhibition succeeds in representing trauma in thoughtful, dense, and yet, enriching way. In her discussion of Mississippi Civil Rights Museum pertinent here researcher Miriam Taylor insists on the pedagogy of discomfort needs to be present to let a visitor break through their conceptual boundaries and engage with the topics involving trauma[8]. In the end it is visitor’s choice to enter the museum, but it is the museum responsibility to present the subject in the most responsible and yet, enlightening manner. Among important criteria Taylor underlines are comprehensive narrative, gallery accessibility, but also transformational power of the presentation. Arguably this last point is and should remain at the forefront of museum experiences when engaging with transmission of traumatic memories. Sarah Softness and Museum of Jewish Heritage clearly succeeds in this as a visitor is gently guided through a life that turned out drastically different by the historical forces outside of one control guided by a strong artistic vision. The exhibition remains accessible to younger viewers although the pedagogy of discomfort might be a little too challenging to 8- or 9-year-olds.

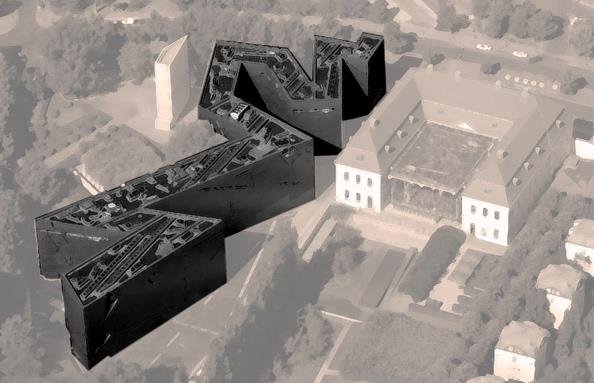

Jewish Museum, Berlin is a different, spatial, manifestation of the recent Jewish history and its traumas. Distinguished building by the renowned architect Daniel Libeskind pushes visitors to consider plight of the diaspora fully uprooted and partially exterminated in the war. The building is consciously dissected by three axes, titled Holocaust, Exile and Continuity. Unexpectedly constructed hallways are aimed to partially disorient a visitor, but also to establish a direct connection through presented objects and media.[9] Pedagogy of discomfort used as an analytical tool by Taylor plays an important role here, but is first implemented by an architect in his design of the space, providing an effective, or dissonant for some critics, ground for exhibitions and the permanent collection. The vast collection of the museum includes 9,500 works of art, 1,000 objects of applied art, 1,500 objects of religious use, 4,500 objects of material culture, 24,000 photographs, more than 1,700 individual collections in the archive, 11,000 volumes in the museum library.[10]

Obviously, presenting such a collection requires a vision over time and 2020 saw the major overhaul of the presentation inside the museum since previously critics agreed that Libeskind’s architecture was so central to the museum that anything presented in it was lost on the visitor.[11] This aspect connects to Renèe S. Anderson’s, concerns when working with museum collection associated with traumatized communities. Anderson, the Head of Collections at the National Museum of African American History & Culture, insists on taking a great care not only on contextualizing the exhibits for the audience, but also upon allowing visitors space for reflection and an emotional journey while supplying all the necessary details and notifications ahead of their experience.[12] As discussed above traumatic memories are part of collective cultures and thus in most cases tend to constitute backbones of communal identity. Exploring these memories through objects needs to be consistent and mindful. Even within the context of the history of the Holocaust representation certain contention and lack of care is noticeable,[13] as various communities are fighting to represent the ‘truth.’

In conclusion of this vast theme within the format of this paper one could outline two main points. Museums that work with representation of the traumatic Jewish history have taken on a sizable burden of not only transmitting painful histories, but also analyzing, storing and researching them for the future generations. The challenge here is how to make the objects count and tell all the stories, how to chose what could stand in for a community – a challenge facing Jewish Museum, Berlin. The second point is that although as museums are striving to bring in an element of enlightenment to the experience with traumatic memories, they still are institutions that work with aesthetics. While discomfort pedagogy could be a viable tool for an encounter with a visitor it should not be done at the expense of presented works and a curatorial vision is still important – a lesson from Boris Lurie exhibition at The Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Sources

aiconservation. “C2c Care Approaching Collections That Evoke Trauma.” YouTube. YouTube, March 31, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OsqltHvGt78.

CUNYQueensborough. “Museums as Places of Trauma and Healing: Processing Visitor Experiences.” YouTube. YouTube, October 6, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LI596ZNmWzg.

Gruber, Ruth Ellen. “Post-Trauma ‘Precious Legacies’: Jewish Museums in Eastern Europe after the Holocaust and before the Fall of Communism.” Visualizing and Exhibiting Jewish Space and History, 2012, 243–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199934249.003.0011.

Hirsch, Marianne. “The Generation of Postmemory.” Poetics Today. Duke University Press, March 1, 2008. https://read.dukeupress.edu/poetics-today/article/29/1/103/20954/The-Generation-of-Postmemory.

Judisches Museum Berlin, Our Collections. Last accessed May 10, 2022 Rertieved https://www.jmberlin.de/en/areas-of-interest

Karkowska, Marta On the Usefulness of Aleida and Jan Assmann’s Concept of Cultural Memory, Polish Sociological Review, No. 183 (2013), pp. 369-388 .

Logan, William Stewart, and Keir Reeves. Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with ‘Difficult Heritage’. London: Routledge, 2009.

Madesn, Kristian Vistrup, For Years, Daniel Libeskind’s Dramatic Jewish Museum Building Upstaged the Poignant Collection It Housed. A New Overhaul Hopes to Change That. Last accessed May 10, 2022 https://news.artnet.com/art-world/redesign-jewish-museum-berlin-2020-1778676

Museum of Jewish Heritage, Members Learn with Sarah Softness: “Boris Lurie: Nothing to Do But To Try.” Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZryN-jZ7V4o

Naumann, Stan, Copans, Richard, Daniel Libeskind, Jewish Museum, Berlin. Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUTkt0z_NTU

Taylor, Miriam, “No Need for Sugar: The Responsibility of Museums to Communities of Trauma.” Last accessed May 11, 2022 https://articles.themuseumscholar.org/2021/12/09/no-need-for-sugar-the-responsibility-of-museums-to-communities-of-trauma%EF%BF%BC/

[1] Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory, Poetics Today.

[2] F.Mazzuchelli, R. van der Laarse, C.Reijnen, Traces of Terror, Signs of Trauma, 2014, p.4

[3] Marta Karkowska, On the Usefulness of Aleida and Jan Assmann’s Concept of Cultural Memory, Polish Sociological Review, No. 183 (2013), pp. 369-388 .

[4] Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory, Poetics Today, p.111.

[5] Ruth Ellen Gruber, Post-Trauma “Precious Legacies”: Jewish Museums in Eastern Europe after the Holocaust and before the Fall of Communism,” p.114.

[6] Museum of Jewish Heritage, Boris Lurie: Nothing to Do But to Try. Last accessed May 10, 2022 https://mjhnyc.org/exhibitions/boris-lurie-nothing-to-do-but-to-try/

[7] Museum of Jewish Heritage, Members Learn with Sarah Softness: “Boris Lurie: Nothing to Do But To Try.” Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZryN-jZ7V4o

[8] Miriam Taylor, “No Need for Sugar: The Responsibility of Museums to Communities of Trauma.”

[9] Stan Naumann, Richard Copans, Daniel Libeskind, Jewish Museum, Berlin. Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUTkt0z_NTU

[10] Judisches Museum Berlin, Our Collections. Last accessed May 10, 2022 Rertieved https://www.jmberlin.de/en/areas-of-interest

[11] Kristian Vistrup Madsen, For Years, Daniel Libeskind’s Dramatic Jewish Museum Building Upstaged the Poignant Collection It Housed. A New Overhaul Hopes to Change That. Last accessed May 10, 2022 https://news.artnet.com/art-world/redesign-jewish-museum-berlin-2020-1778676

[12] aiconservation. “C2c Care Approaching Collections That Evoke Trauma.” YouTube. YouTube, March 31, 2022.

[13] For further discussion see the chapter on Auschwitz-Birkenau in Logan, William Stewart, and Keir Reeves. Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with ‘Difficult Heritage’. London: Routledge, 2009.

Image: Aerial view of the Jewish Museum, Berlin. The zig-zag geometry of Daniel Libeskind’s building is based on distortions of the Star of David. Source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326566044_Architecture_as_Music_A_personal_journey_through_time_and_space#pf3